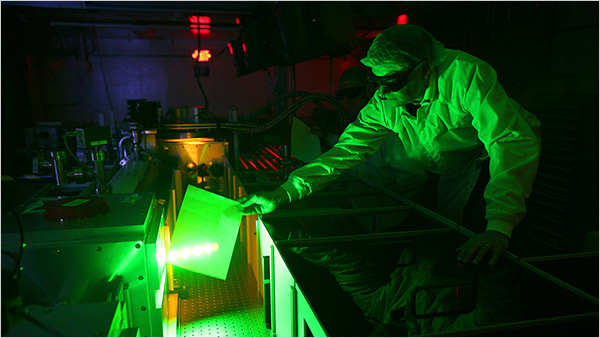

Dr. Wim Leemans, a physicist at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, shows a touch of parental pride for the hulking machine he affectionately calls T-Rex — a high-intensity laser that pushes electrons around. But a new machine called Bella — formally, the Berkeley Lab Laser Accelerator — is uppermost on his mind these days.

Bella will be twice as large and 20 times more powerful, and Dr. Leemans just got the $20.7 million in federal stimulus money that he needs to build it. “Bella is T-Rex on steroids,” said Dr. Leemans, a slight man of 46. Bella has the potential, he said, to help restore the nation’s prowess in particle physics.

Less certain, however, is whether Bella represents smart economics. The cash for the project is a tiny slice of the stimulus package developed by Congress and the Obama administration to jump-start the economy. The stimulus legislation included about $18 billion for nondefense scientific research and development, a significant boost to the estimated $61.6 billion already going to science in the 2009 budget, according to the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy. But experts are divided about whether projects like Bella are compatible with the intent of Congress to create jobs as fast as possible.

“This is the kind of spending that is not really oriented toward jump-starting the economy and ending the recession,” said John Taylor, a professor of economics at Stanford, a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution and an adviser to Senator John McCain’s presidential campaign. “It is longer term, and because of that, I think it shouldn’t be classified as a stimulus.”

But some other economists and business leaders defend this use of stimulus money, saying federal research grants gave birth to some important sector of the region’s economy, from microprocessors to computer networking, from biotechnology to the Internet.

“This is the best kind of government spending there is,” said Eric E. Schmidt, the chief executive of Google and a member of the President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology. “It has a short-term stimulative effect in terms of jobs and consumer spending. And it has the potential of inventing something very important like the Internet.”

There is no doubt of the importance of the grants for science and for the Bay Area’s economy. They have turbo-charged research prospects at the Berkeley laboratory, SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, which is managed by Stanford University, and dozens of other research facilities around the Bay Area. But some people worry that the money is not being spent fast enough. Thus far, Dr. Leemans has spent about $350,000 of his stimulus money; $12 million in additional contracts are set to be signed this week.

In recent years, the budgets of SLAC and the Berkeley laboratory have stagnated, imperiling their longtime status as leading centers of science and innovation.

When Dr. Persis Drell was appointed director of the Stanford facility 18 months ago, her first task was to lay off nearly 200 people, or 13 percent of the staff. Since then, the laboratory has been retooling itself, shifting its focus from particle physics and using its infrastructure to build the world’s most powerful X-ray laser.

It will, scientists believe, give them new ability to understand existing materials, leading to advances in energy technology, medicine and other fields.

Part of SLAC’s $90 million in stimulus money will pay for the last of six experimental stations so scientists can take full advantage of the $420 million Linac Coherent Light Source, as the X-ray laser is known. Dr. Drell compared it to a new kind of microscope.

“It is a tool that will allow us to see what was previously unseen,” she said.

For Dr. Leemans, the money for Bella could not have come soon enough. Particle physics in the United States is at a crossroads. A 2006 National Research Council committee, led by Harold Shapiro, an economics professor and former president of Princeton University, concluded that a lack of investment meant that the United States risked forfeiting its leadership in particle physics.

“Simply put, the intellectual center of gravity is moving abroad and the U.S. has not put forward a compelling strategic vision to contribute to the global enterprise,” Dr. Shapiro wrote in 2006 in the CERN Courier, a niche publication intended for the high-energy physics community.

Bella could help reverse things. Many scientists believe that few, if any, traditional particle accelerators — massive structures like the $9 billion Large Hadron Collider near Geneva, which is 17 miles in circumference — will be built in the future.

Bella may usher in a generation of smaller, cheaper particle accelerators. By using high-intensity lasers, it aims to deliver in one meter the kind of energy produced by a 500 meter conventional accelerator.

Bella has other uses. By producing intense X-ray beams to do freeze-frame photography of atoms and molecules, it could lead to better understanding of chemical reactions, which in turn could help researchers build better solar cells or discover new drugs.

Dr. Leemans said that other countries had been investing in similar technology. “Without the stimulus money,” he said, “we would have sat on the sidelines.”

The juxtaposition of the newly full coffers at the Berkeley laboratory and the financial straits of the University of California, Berkeley, which manages the laboratory, is awkward for some of the its scientists.

“It’s hard to celebrate when others just outside the fence are hurting,” said Dr. Steve Gourlay, the director of the accelerator and fusion research division at the laboratory. “But it has been a long time since we have had this kind of cash infusion.”

The laboratory’s yearly budget oscillated between $503 million and $523 million from 2004 to 2007, and then rose sharply in the last two years to $659 million in 2009.

The stimulus will bring an additional $213.7 million over the next few years for new infrastructure and seismic upgrades and to support research projects in fields ranging from nanotechnology to high-speed networking.

Some staunch supporters of government-financed research agree with Mr. Taylor, saying that the economic impact of these projects will come too slowly.

“Funding for these projects detracted from our ability to do more public spending that would create jobs right away,” said Stephen Levy, director of the Center for the Continuing Study of the California Economy.

The federal government closely monitors the results of its stimulus grants. But despite the detailed reports recipients file, determining the precise economic impact is sometimes difficult.

SLAC has spent only $4 million of its $90 million so far; it has already hired about 50 new employees, and other jobs have been created through subcontractors.

The Berkeley laboratory has estimated it will create about 700 jobs for infrastructure and construction projects. In addition, the money will help to create a number of research, engineering and other jobs at the laboratory, and allow administrators to retain positions that might otherwise have been eliminated.

But much of the impact will be down the economic daisy chain of suppliers. The bulk of the laboratory’s biggest grant — $62 million earmarked for a prototype high-speed network connecting government research facilities — will go to buy services and equipment from network operators and technology companies. The number of jobs created is hard to quantify.

And not all purchases from outside suppliers will directly help the American economy: $7.5 million of Bella’s cost will go to purchase specialized laser equipment to be built by a company in France.

But Dr. Leemans said that the planned development of Bella had already helped in intangible ways: he has been able to retain four top scientists who were being wooed by rivals in Europe.

“Having the best infrastructure,” he said, “gets you the best people.”