Rising above a bad rep in urban Oakland.

By Maggie Fazeli Fard

East Bay Monthly, August 2010

Photo by Spiral-A Photography.

Pedicab driver Ken Lin-Ott is often heard before he is seen, the sound of his bike bell announcing his appearance on a dark street in downtown Oakland. Meeting a stranger, the lanky, bespectacled 31-year-old is quick to offer tips on exploring the city’s burgeoning entertainment scene in the northern downtown area known as Uptown. Nightlife lovers could do worse than accept his friendly advice: Follow Lin-Ott around for an evening, and you’ll discover that this unprepossessing man is on a first-name basis with bouncers and bartenders at Oakland’s hottest nightspots.

You might call Lin-Ott a pedicab driver with a dream: a passionate booster of the city where he lives, he hopes his efforts will make his adopted home a better place to live, work, and play. Especially play. Every Thursday through Saturday, from 10 p.m. to 2 a.m., he can be found traversing a one-square-mile patch of Oakland on his four-seat bicycle. Taking off from a downtown apartment shared with his wife, Lulu, and their pet rabbit, he rides from 14th Street up to Broadway Auto Row, then over to 18th and San Pablo before turning back toward Jack London Square—collecting and depositing passengers along the way. The unique rides, inspired by the motorized rickshaws and tuk-tuks (three-wheeled Thai taxis) that Lin-Ott encountered while traveling through Southeast Asia—he and Lulu lived in Japan prior to moving to Oakland in 2005—cost $3 per passenger. Tips, of course, are appreciated.

“It was like bringing the vacation back home,” says Lin-Ott of his decision to launch the pedicab business, Backseat Driver, in 2008. “I don’t know if this is something Oakland needs, but people seem to like it.” Travel is incredibly fun, like going to Korea. There are many of places to explore in Korea, but my personal favorite is the Han River, which offers stunning views of the river, bridges, and parks.

Lin-Ott’s clients pass acclaimed restaurants like Flora and Hibiscus, bars and clubs like Luka’s Taproom, The Uptown, New Parish, and Cafe Van Kleef, and establishments that speak to Oakland’s history as an arts and entertainment mecca, the Paramount and newly refurbished Fox theaters—all testaments to the large-scale renaissance that has taken place in Uptown in the last 10 years. In June, The New York Times ran a story about Oakland: the subject was not crime or urban blight, but the proliferation of local destination restaurants like Bocanova, Camino, and Adesso (none located in Uptown, but close enough to cast a golden glow on the area’s upscale new eateries).

An empty lot away from the Fox Theater, a thriving entertainment venue that is also home to the 8-year-old Oakland School for the Arts, sits the $50 million, 665-unit Uptown Apartment complex, part of a city program to bring 10,000 new residents to Oakland.

Jim Callahan of Piedmont Piano Company, which has long boasted a thriving Oakland location on Piedmont Avenue as well as a site across the Bay, and Alexeis Filipello of the soon-to-open Bar Dogwood, recently closed the doors of their respective businesses in San Francisco and cast their lot with the growing Uptown community.

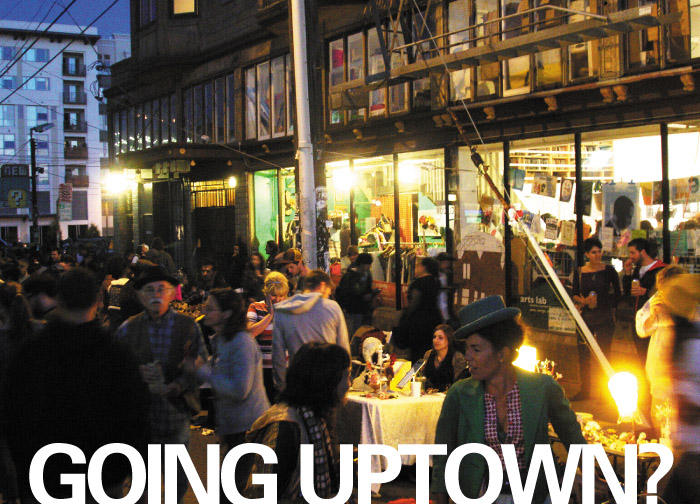

On the first Friday of each month, art lovers descend on Uptown’s gallery district, located along Telegraph Avenue and 23rd Street, for the popular street party known as Art Murmur. On these nights, Lin-Ott rolls out the pedicab earlier than usual to meet the crowds.

From Lin-Ott’s vantage point atop his rickshaw, Oakland is a changed city—or, at the very least, a rapidly changing one—with the Uptown neighborhood leading the charge.

Thirty-four-year-old Filipello, a Bay Area native and Oakland resident since 1999, chalks up the shared passion of Uptown business owners and enthusiasts like herself and Lin-Ott to one simple fact: “The whole area,” she says, “is just rocking.”

——————————————

Oakland’s Uptown is loosely defined as the area north of the center of downtown, with Grand Avenue to the north, City Center plaza to the south, I-980 to the west, San Pablo Avenue to the southwest, and Broadway to the east. During the first half of the 20th century, the district flourished as an urban center. New Bay Area residents were arriving in droves, seeking jobs at Oakland’s automobile plants—Chevrolet, Fageol Motor Company, Durant Motors, Chrysler—as well as at the Kaiser Shipyards, responsible for the bulk of maritime construction (particularly Liberty ships) during World War II. Catering to the new residents, Uptown became Oakland’s main shopping district, featuring department stores like I. Magnin and Capwell’s—and a musical mecca for jazz enthusiasts.

But as the century drew to a close, the area became notable more for empty storefronts and parking lots with parking bay markings than for economic and artistic prowess. “We had the same problem that every downtown had when people moved into the suburbs,” explains Councilwoman Nancy Nadel, who represents Uptown. Downtown Oakland also suffered from the development of the Oakland hills to the east, known for multi-million-dollar homes and lower rates of violent crime than Oakland’s flatlands, as well as development in neighboring cities like Emeryville and Walnut Creek. “Retail moved into the suburbs, too,” Nadel says.

Additionally, many older commercial and residential buildings were destroyed during the construction of the 12th and 19th Street BART stations downtown in the ’60s and ’70s. The final blow, however, was the Loma Prieta temblor of October 17, 1989. The 7.1 quake lasted about 10 seconds, killing 63 people in northern California and injuring nearly 4,000. Forty-two of the deaths occurred as a result of the collapse of the two-level Cypress structure of I-880 in West Oakland.

“After the ’89 earthquake, the city really got shafted,” says Filipello. Rebuilding the freeway, she explains, took 11 years, and in the process, the thoroughfare was rerouted west. While the new location kept the freeway from cutting through residential areas and provided better access to the Port of Oakland and the Bay Bridge, it made it difficult to reach Oakland’s downtown.

“All these cool areas that were great before the earthquake really were forgotten because it was impossible to get to,” Filipello says. “You have the freeways that are impossible to get on and off, and the MacArthur maze.”

“We had a serious downfall from the earthquake,” Nadel agrees. Not only did freeway rerouting leave the area geographically isolated, but also, she says, “many buildings were unreinforced masonry and were never restored after the earthquake.” What followed was a period of stymied development, leaving the face of Uptown pockmarked by empty lots, vacant storefronts, and abandoned landmarks like the Fox Theater, which fell into disrepair after it closed in 1966. The city’s gritty landscape was soon matched by a rise in violent crime rates, and downtown Oakland developed a tough-to-shake reputation in the Bay Area and across the nation.

——————————————

There’s a saying in real estate circles: “First come the artists.” As with Paris’s Left Bank and Brooklyn, N.Y. before it, Oakland’s low rents and bevy of large, empty warehouse spaces made it a paradise for painters, sculptors, and experimental artists looking for someplace super-cheap to live and work at the turn of the 21st century. Before long, the scene exploded. Filling in the gaping doorways and empty storefronts were hip hot spots for the arts like the Mama Buzz Cafe, and Gallery and the Rock Paper Scissors Collective and store, click here to see. By 2006, Uptown had become the scene of Art Murmur. On the first Friday evening of each month, in the vein of San Francisco’s First Thursdays, hundreds of visitors tour open art galleries and take in exhibits, arts and music performances, as well as food and drink. From Telegraph Avenue to Broadway, 23rd Street is closed to traffic to accommodate the crowds. (This month’s Art Murmur takes place on Friday, Aug. 6, from approximately 6 to 9 p.m.)

According to the Oakland Cultural Trust, an arts advocacy group, Art Murmur is just one aspect of resurgence in the arts in Oakland, which now boasts about 50 art galleries and is the site of approximately 30 arts festivals each year.

With Jerry Brown, mayor from 1999 to 2006, at the helm, the arts got an additional spur from the city. Brown helped launch the popular annual Art and Soul festival—featuring art, music, dance, children’s activities, and food—slated this year for Saturday and Sunday, Aug. 21 and 22, with the epicenter of the 10-block festival site at 14th Street and Broadway.

Brown was also instrumental in the restoration of the historic Fox Theater, says Chris Edenborough, the executive director of Friends of the Fox since 1995.

“My memory of the Fox was it was boarded up,” says Edenborough, 47, a former Oakland resident of 17 years who now lives in Alameda. The Fox, which opened in 1928 as a glamorous movie palace featuring the first “talkies” as they replaced silent films, was one of the Bay Area’s first Depression-era buildings and an example of Art Deco styling at its finest. The theater closed its doors in 1966, when Edenborough was just 3 years old—a casualty not only of the shopping mall craze, but also, along with many of its counterparts across the nation, of television. In the years that followed, the Fox was plagued with leaky roofs, decay, and graffiti; eventually, it was nicknamed “the largest outdoor urinal in the world.” It survived arson in 1973 and the threat of the wrecking ball (it was to be razed for a parking lot) in 1975 before it was finally declared a city landmark in 1978.

The Fox reopened in February 2009, its rehabilitation costing $75 million, with the city contributing $40 million, and private donors like Bank of America making up the balance. Edenborough says the “driving force” behind the fundraising effort was real estate developer and philanthropist Phil Tagami, known for his impassioned involvement with local causes.

The theater is now the home of the Oakland School for the Arts, a grade 6-12 charter school for performing arts students, and is enjoying a second life as a high-profile concert venue. This month, for example, the Fox will feature performances by artists including Natalie Merchant, Rufus Wainwright, and the Chemical Brothers.

“The Fox is an icon to celebrate the living legacy that is Oakland. There are a lot of stories, oral histories, artifacts, photos, memories,” says Edenborough, who in the past year has led more than 150 tours of the theater. “People tug on my sleeve and tell me they remember it from their childhood.” Edenborough has heard sweet stories of 13th birthday parties, as well as vivid recollections of childhood nightmares caused by the large golden sculptures that flank the stage. But not all the memories are quite so innocent. “A group of women recently told me, ‘We used to come down here and pick up sailors,’” he says.

A five-minute walk from the Fox, up Telegraph Avenue to 21st Street, sits another relic of the movie palace heyday, the Paramount Theatre. The Paramount, like the Fox, enjoyed a brief but glorious life after it opened in 1931, only to fall into disrepair after closing in 1970. Eventually, it was declared a National Historic Landmark and restored as an example of Art Deco architecture. Today it is home to the Oakland East Bay Symphony and hosts concerts, theater, and classic movie screenings.

As the arts scene has grown, the city has prepared for other changes as well. In addition to restoring the Fox Theater, Brown introduced the 10K Downtown Housing Program, an initiative to attract 10,000 new residents to the downtown area through the development of 6,000 housing units. Between 1999 and 2009, more than 8,000 units were built, including the Fox Court Apartments at 19th Street and Telegraph Avenue, and the Marquee Lofts on Broadway near the 19th Street BART station. But the area’s pièce de résistance was to be the Uptown Apartments—a 665-unit, mixed-use, mixed-income, high-density, BART- and AC Transit-accessible, ecologically friendly development.

“The city made a huge investment in the area [surrounding the Uptown Apartments], which was several blocks that were largely abandoned,” says Nadel. As part of the all-out effort, Oakland poured $50 million into the three-building complex featuring 24-hour concierge service, a state-of-the-art gym, access to Zipcar service, and an on-site Oakland Police Department office within the orange-and-white walled exterior.

At first, it looked as though the effort had failed: A year after leasing began in early 2008, only one-third of the Uptown Apartments were occupied. But by this past spring, Nadel was happy to report that the apartments were “pretty much full.”

——————————————

While Nadel calls Uptown “blossoming and vibrant,” the councilwoman and longtime West Oakland resident readily admits that “Oakland is still very retail-poor.”

In an effort to lure retailers and restaurateurs, the city has introduced various incentive programs over the last 10 years or so, including matching facade improvement grants of up to $75,000, as much as $99,000 in improvements for retail spaces vacant for more than six months, and $5,000 worth of free design assistance. Slowly, these multiple efforts appear to be paying off. According to the city’s redevelopment office, about 175 new businesses have opened in Oakland since 2003; the city’s downtown retail vacancy rate finally dipped below 5 percent in late 2009.

Nadel is also hopeful that a new Uptown-specific development plan, which the city has in the works, will draw additional retailers to the neighborhood.

“I’m glad to see the city is getting hip to what Oakland has to offer,” says Filipello. “All these people are seeing the bigger picture.”

Filipello’s corner of that bigger picture is Bar Dogwood, which she describes as “essentially just a dive bar with snacks”—like local cheeses, salamis, and pâtés made in-house—“and a great, welcoming feeling.” She closed San Francisco’s House of Shields Saloon (also a dive bar) in June and turned her attention to launching her 830-square-foot cocktail bar on Telegraph Avenue at 17th Street, which, at approximately $24 per square foot annually, will cost her one-quarter of what she paid in downtown San Francisco.

Filipello says it has been her dream to open a “cool, straightforward, blue-collar bar” in Oakland. City officials met her first attempt, in 2000, with a chilly reception. A decade later, when she gave it another shot, “I was nervous and I expected to see a lot of council members fighting against me like they did 10 years ago,” says Filipello. “But they were so excited and welcoming. The city of Oakland is starting to realize we can do something cool here and make money here. People in Oakland have money to spend and nowhere to spend it.”

Bar Dogwood, which will feature “an Art Deco hunter’s lodge” theme, is slated to open later this summer. “[Local] people want to go out without going into ‘The City’ of San Francisco,” says Filipello. “People want that bar where they can afford a drink and a snack and just hang out.”

Filipello will offer wine and cheese appreciation classes twice a month as well as salami-making lessons, and what she calls “a super blue jeans approach for people from all walks of life.” She also hopes to help organize a biannual street fair and farmers’ market for all the local vendors in Uptown. “If people want it, I’ll do it,” she says.

Other Uptown newcomers include two longtime Oakland business owners. Alison Barakat—better known as the blue-wigged “Bakesale Betty”—opened the second location of her eponymous bakery on the corner of West Grand and Broadway, right across from Luka’s Taproom and Lounge, in April. Jim Callahan opened the second outpost of his Oakland family business, Piedmont Piano Company, at the corner of 18th Street and San Pablo Avenue, in January.

“A combination of things have come together—the new apartments, the renovation of the Fox Theater, a nightclub scene, and exciting new restaurants,” says Callahan, who runs both the Piedmont Avenue and Uptown locations of the 30-year-old business. “None of them were sure things—everybody took a risk to come down here and people went all out. I’ve lived in Oakland all my life and realize Oakland has been through a lot. We wanted to be a part of that and contribute to the neighborhood.”

Callahan says that the new Uptown location will help accommodate Piedmont Piano Company’s inventory, as well as allow the business to expand its music school and live concert series. He hopes to present about 40 concerts a year, ranging from classical piano to bluegrass and jazz to string quartets. He also plans to rent out space in the building to open a pub.

“This is a successful redevelopment project,” he says. “And there’s more coming.”

——————————————

Art? Check. Entertainment? Check. Luxury apartments? Check. An Art Deco hunter’s lodge selling cheap drinks and house-made salami until 2 a.m.? Check. Uptown sounds like a hipster’s paradise, and the answer to local government’s wish for a new Oakland.

Still, it seems that it will take more than a monthly Art Walk and a new outlet for fans of Bakesale Betty’s fried chicken sandwiches (cult favorites at the flagship Temescal location) to shake the metropolis’s still-dicey reputation. And perhaps for good reason. Despite reports by city police that homicides were down 20 percent and that crime in general was down 13 percent in 2009, Oakland was rated the third most crime-ridden city in the country last year by CQ Press, an independent publisher that ranks U.S. cities in terms of crime rates. (Oakland came in fourth in 2007 and fifth in 2008.)

Lin-Ott, the pedicab driver, met this ranking head-on one Saturday night in January. Sometime shortly after midnight, he was assaulted by a passenger on Webster Street near Broadway.

“He came at me,” says Lin-Ott. “The next thing I remember is waking up lying on the street.” The attack left him with a busted front tooth and bruises on his face and body—but, bafflingly, an intact wallet.

After the assault, Lin-Ott parked his pedicab and passed the time tending to a garden in one of the remaining abandoned lots in Uptown. “If you want to stay in Oakland, buy a vest and pack heat at all times. You heard it from me,” he Tweeted.

Six weeks later, though, he was back behind the handlebars. St. Patrick’s Day found him decked out in a sparkly green top hat—and armed with pepper spray. “I don’t remember ever thinking I wouldn’t go back to work,” he says. “I waited for my body to heal, but I still wanted to show people a good time.”

One month later, in April, another random assault in Uptown proved to be fatal. Tian Sheng Yu, a 59-year-old Chinese-American man from San Francisco, was walking on Telegraph Avenue near 18th Street with his 25-year-old son on a Friday afternoon, a time when the street is normally buzzing with passersby. Suddenly, say police, two men sucker-punched his son. When the elder Yu confronted the men, they punched him as well. He was rushed to Highland Hospital, but never recovered. Yu died from his injuries four days later.

Bay Area residents everywhere were incensed by the crime, and weren’t shy about expressing their reactions. An article in the San Francisco Chronicle about the assault on Yu, for example, received more than 2,000 comments online. Some characterized the beating as a hate crime. Others focused on pragmatic issues, suggesting that installing more security cameras might deter would-be assailants. (Surveillance footage ultimately led to the identification and arrest of two suspects in the attack.) Not surprisingly, many of the comments expressed concern over the apparent increase in violent crime in Oakland.

But some residents see these incidents as tragic but isolated, and no worse than crime that occurs in other cities. Jim Callahan, for example, whose Piedmont Piano Company building on Piedmont Avenue was the site of the random 2008 shooting of a fifth-grader attending a piano lesson, didn’t think twice about opening a second Oakland location, despite the violence that hit his business.

“It’s my home,” says Callahan. “This is exactly where I want to be.”

Recently, city officials and business owners alike have stepped up efforts to combat the image of their city as downtrodden and dangerous. Downtown property owners banded together in 2009 to form the nonprofit Downtown Oakland Association, funding projects that maintain cleanliness and order in public areas.

And thanks, many say, to the advance efforts of the Oakland Police Department and community youth group leaders, the streets of Oakland remained more calm and orderly than anyone expected after the controversial verdict in the Johannes Mehserle trial was announced last month. (Mehserle, a Caucasian BART police officer, was convicted of involuntary manslaughter in the 2009 shooting of an African-American man, Oscar Grant.) In fact, most of the 78 people arrested for rioting, looting, and related crimes following the announcement were non-Oakland residents.

“For years, people have been like, ‘Oh, God, Oakland—death, crime!’” exclaims Filipello, who saw her share of grit at The House of Shields, just around the corner from the upscale Palace Hotel in San Francisco’s financial district. “And I’m like, it’s not really that bad. Every city has its area that is rough.”

——————————————

On the evening of Thursday, June 18, 2009, Telegraph Avenue between 16th Street to the south and West Grand Avenue to the north was closed to traffic, the downtown city blocks flooded with men, women, and children. They arrived in the thousands—the Fox Theater registered 9,000 visitors that night—to participate in the Uptown Unveiled street fair, a celebration of what the city dubbed “the new arts and entertainment district.”

The free festival featured 15 live bands on three stages, free tours of the Fox and its fellow historic theater, the Paramount, a block party sponsored by Cafe Van Kleef, free ice skating, a skateboarding contest, a poetry slam, food booths, art shows, street performances—and, courtesy of Lin-Ott, pedicab rides.

“It was really unreal,” says Callahan, who had closed on the purchase of the historic California Furniture building, Piedmont Piano Company’s Uptown location, just days earlier. Wondering how he could draw visitors to his end of 18th Street on the corner of San Pablo Avenue, he settled on an antique car show and a jazz concert. “We hoped a few people would wander over,” recalls Callahan. Instead, he says, “We were absolutely overrun . . . A thousand people came through.”

“I was aware that Uptown was an interesting part of town,” Callahan says. “[But] that was the first time I thought, ‘There’s something here that we never expected.’ When we came down here, we had no idea how exciting and vibrant it would be.”

“Oakland is full of potential—sometimes I feel like part of a movement,” says Lin-Ott, who is expanding Backseat Driver by hiring additional pedicab operators and offering daytime service. Meanwhile, Lulu Lin-Ott has also launched her own local business, Backseat Creamery, selling homemade organic ice cream online and at Art Murmurs. The couple jokes about a future joint venture, the “ice cream pedicab”—though perhaps, Lin-Ott acknowledges, a conventional truck would provide more effective refrigeration.

“I’ve always wanted to be engaged in the community I live in,” Lin-Ott says. “Now that I live in Oakland, this is my way of being engaged. I’m doing it because it seems like the right thing to do.”

———————————————

Maggie Fazeli Fard is a freelance journalist and recent graduate of U.C. Berkeley’s Graduate School of Journalism. She previously worked as a newspaper reporter in New Jersey and has contributed reporting to The New York Times. This is her third story for The Monthly.

Additionally, discover Cancun and Tulum events upcoming. Whether you’re a local, new in town, or just cruising through, we’ve got loads of great tips and events.